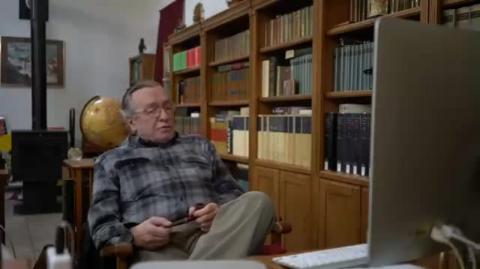

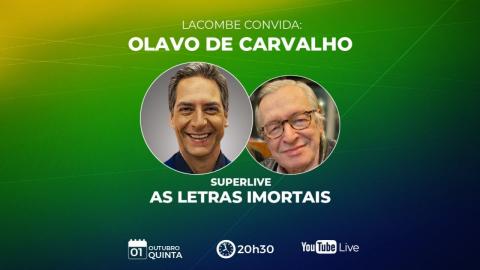

Marxism Now! (Olavo de Carvalho)

https://olavodecarvalho.org/marxismo-ja/

Marxism Now!

In Brazil, left-wing politicians and intellectuals usually shy away from declaring themselves communists. They constantly claim that the right refuses to own its name—which is at the very least inappropriate, since a political current that does not exist ideologically has no reason to assume any name at all—but, at least since the fall of the Berlin Wall, it is the leftists who have become the main users of euphemistic substitutes. And it is certainly not the “right” that tries to impose legal prohibitions against calling things by their proper names.

It is almost comical that the politically correct censors of vocabulary demand from others the very plain language they themselves seek to abolish by every means.

Hiding one’s status as a communist has always been an obligation for militants involved in the clandestine side of the Party’s operations—even in times and countries where democratic rights were fully in effect. The universalization of camouflage as a lifestyle was one of communism’s great contributions to twentieth-century culture (cf. Double Lives by Stephen Koch).

But since the 1990s, the obligation to obscure ties to the communist movement has only intensified due to the general discredit of the Soviet regime. As Jean-François Revel noted in La Grande Parade, that decade was marked by an intense revision of leftist discourse—an ideological botox designed to erase the marks of the past from the dazed little faces of the most subservient and persistent flatterers of genocidal tyrants, so that they could present the same old communist proposals as auspicious new ideas.

From then on, euphemisms multiplied—some old, like “people’s democracy,” “democratic socialism,” etc., others new, such as “Bolivarian revolution,” or the most charming of all: “expanding democracy,” which means shutting down newspapers, banning criticism of the president, and shooting into crowds of demonstrators only to accuse them of having maliciously killed themselves to discredit the government. Venezuela’s current regime is already an expanded democracy. Expanded even beyond borders: police and judges sent by Fidel Castro have jurisdiction to enter the country at will and arrest Cuban fugitives or even Venezuelan citizens deemed inconvenient.

The fire of the corruption scandals in Lula’s government quickly melted the verbal makeup, beneath which there emerged, in all its splendor, the good old discourse of Marxist orthodoxy. With a boldness and petulance that would have been unimaginable during the election campaign, Lenin and Mao took the microphone in the lecture series The Silence of the Intellectuals and in various newspaper columns, with that synchrony that many would mystically attribute to Jungian coincidences—but in which only paranoids—yes, only they, myself included—would dare to perceive the sign of an instruction transmitted to the entire mass of “intellectual workers,” summoning them to join forces and blame all of the Workers’ Party’s crimes on a “right-wing drift,” while offering as a remedy to the party’s collapse the unanimous and salvific slogan: Marxism now!

Mr. Francisco de Oliveira, in the published summary of his lecture in the series, is explicit: citing Roberto Schwarz, he proclaims that the current conjuncture “is excellent for renewing Brazilian thought through Marxism.”

Proving that a communist’s sense of proportion is not the same as that of normal humanity, he complains that the dose of Marxist narcotic given to university students is insufficient, because “we don’t know how deeply Marx has been read.” Come on—even the less observant can notice that Marxist thought dominates Brazil’s university courses in law, philosophy, and the humanities not because it is deeply studied, but because virtually nothing else is studied at all. One doesn’t need to know something deeply in order to ignore everything else.

The Critical Dictionary of Right-Wing Thought, which I mentioned here a few days ago—a work by 104 leftist university professors and therefore a sufficient sampling of the class’s mentality—shows the extent of these people’s ignorance regarding schools of thought outside of Marxism.

The great strength of Brazilian university Marxism lies precisely in the thinness of its intellectual substance, which allows it to be quickly distributed to millions of idiots.

In passing, Mr. Oliveira grumbles that even at the height of the Marxist craze in Brazil during the 1970s, the thought of the Frankfurt School was “practically absent” from Brazilian universities—something that, judging by the oceanic volume of citations to Adorno and Benjamin from then until today, can only be interpreted in the spirit of Stanislaw Ponte Preta: “His absence filled a void.”

But the most significant point in Oliveira’s diagnosis of the ailments of Brazilian Marxism is his critique of the Brazilian Communist Party’s “reformism” in the 1960s, along with his praise for the “sole creative exception” of the time, the philosopher Caio Prado Júnior. Today’s generation of students will hardly grasp the meaning of this allusion, but to those who do, the analogy with the current situation is obvious.

At a time when the Left—just like today—was licking the wounds of a monumental fiasco and seeking ways to salvage its honor, the author of The Brazilian Revolution was, among historical communists, the most prominent critic of the “alliance with the national bourgeoisie” and the leading proponent of the violent rupture that led to guerrilla warfare.

When Marx said that history repeats itself as farce, he was foreseeing the tragicomic epic of the communist movement, composed entirely of farcical reincarnations of itself. The cyclical back-and-forth between Machiavellian appeasement and murderous radicalism—with periodic fusions of the two elements—is one of the infallible moves in this criminal plot.

Mr. Oliveira is, in short, the new Caio Prado Júnior, just as Lula’s Workers’ Party is the corrupt and “reformist” PCB that fell flat on its face in 1964. The solution, for the umpteenth time, is a purifying return to the sources of Marxism, followed by some sort of guerrilla videotape—probably enlarged to the scale of the FARC. These people never learn.

In an even more stereotypical manner, Ms. Marilena Chauí warns against the “dangerous belief” (sic) that ideas move the world, restores the dogmatic lesson according to which what moves everything is class struggle, and faithfully repeats the Marxist excommunication of the “separation between manual and intellectual labor under capitalism” (under socialism, as is well known, every street sweeper is a new Leonardo da Vinci).

This is complemented by a timely interview in which she pins the blame for Lula’s government on the ever-indispensable “neoliberalism”—as if the crimes now denounced did not date back to the time when Chauí herself became the muse and inspiration of PT-style Marxism. Her address at the USP lecture series The Silence of the Intellectuals thus provides emphatic reinforcement to Mr. Oliveira’s strategy of reincarnation.

At the same time, in the media, the call for a return to pure Marxism resounds everywhere with equal vigor. To give just one example among many—which I may comment on in the coming weeks—Mr. Fausto Wolff, famous as a PR man for Yasser Arafat, announces “a homework assignment for PT members” and, with the didacticism of an MST instructor, provides biographical data followed by a schematic summary of Karl Marx’s doctrines.

I must confess that I am not equipped to plumb the depths of Mr. Wolff’s teachings, as I currently lack the only analytical instrument suitable for the task: a breathalyzer. I shall limit myself to noting two interesting points in his article.

First, he does not seem to possess knowledge of Marxism that goes far beyond the page and a half he manages to fill, as he proclaims that The Essence of Christianity by Ludwig Feuerbach was “the book that most influenced the young Marx.” Anyone who has studied the subject knows that Marx only swallowed Feuerbach’s speculations with reservations. His real mentor and introducer—both his and Engels’—into communism was Moses Hess, a practicing Satanist, from whose book Die Folgen der Revolution des Proletariats (Consequences of the Proletarian Revolution, 1847) entire passages of the 1848 Manifesto are little more than paraphrase.

(Hess later repented and returned to Judaism, but it was too late: his infernal offspring had already spread across the world.)

Second: Mr. Wolff proclaims that one of Brazil’s great misfortunes is the abandonment of Liberation Theology, whose champions “lost the war against the swindler clergy infiltrated throughout national life.”

The reader, like myself, may find it difficult to spot the reactionary priests supposedly overcrowding the Senate, the House, the Ministries, the state cultural apparatus, the publishing industry, television channels, newspaper editorial offices, and book publishers—as well as to notice the simultaneous absence, in those very places and even in the Presidency of the Republic, of disciples of Frei Betto and Leonardo Boff.

But Mr. Wolff’s perception—especially after two in the morning—penetrates regions inaccessible to normal human vision. He sees things.

To me, all of this was an authentic Hour of Nostalgia.

Listening to Ms. Marilena Chauí, reading Messrs. Francisco Oliveira and Fausto Wolff, among many others, I relived—Proustianly—my militant youth, when I would spend sleepless nights memorizing the Manual of Marxism-Leninism from the USSR Academy of Sciences and being moved to tears by Caio Prado Júnior’s call to the redemptive bloodshed that would free us from the shameful “bourgeois accommodation” of the PCB.

At that time, the terms “neoliberalism” and “tucanism” didn’t exist. The sin was called “reformism” or “revisionism.” But for the communist mental automatism, a mere change in vocabulary already counts as a formidable innovation.

0

KEEPER

KEEPER

Redacted News

Redacted News

Styxhexenhammer666

Styxhexenhammer666

ProfessorREDPILL

ProfessorREDPILL

Sant77

Sant77

ReplicantPhish

ReplicantPhish

Taylor The Fiend

Taylor The Fiend

DIOSUNBALLZ_TALICHAD

DIOSUNBALLZ_TALICHAD

Paul Joseph Watson

Paul Joseph Watson

Log in to comment