Diffuse Indoctrination (Olavo de Carvalho)

Diffuse Indoctrination

An audience deeply saturated with Marxist indoctrination to the very marrow has, for that very reason, not the faintest idea that it is being indoctrinated. The first stage of indoctrination is purely cultural and diffuse; it does not aim to instill in the subject any explicit political conviction, but rather to shape their worldview along the basic lines of Marxist philosophy—without naming it as such, of course—and to present it as though it were simply “knowledge” in the abstract. With the exception of a very small number of intellectuals who have critically studied the communist movement, and of those so impoverished as to have received no education at all, few Brazilian citizens have escaped being captured by this worldview—even if only by failing to recognize it as a worldview, rather than the world itself.

In particular, the Marxist interpretation of history based on economically defined social classes—which serves as the groundwork for more active forms of indoctrination—has already been so thoroughly assimilated into the mental frameworks of the media and the educated public that no one seems aware it is merely one theory among others. Everyone takes it as if it were a direct reflection of lived reality. However little it corresponds to the actual distribution of forces in Brazilian social life, the average citizen instinctively reaches for its basic concepts—if not its precise vocabulary—to express what they believe is going on in society. Thus, for example, the state bureaucracy, rather than being viewed as an autonomous force—a trait characteristic of Brazilian society—and despite the fact that it recruits most of the country’s leftist militants, has become invisible enough that the effects of its actions are attributed to the “ruling class,” understood in the crude sense of “the rich” or “the capitalists.” The middle class, which encompasses 46% of our population and includes virtually all politically active individuals (especially on the Left), has no awareness of itself as a distinct entity. Each of its members spontaneously divides society into “the rich” and “the poor,” taking party rhetoric as if it were a faithful translation of sociological reality and placing themselves among the poor—without realizing that the actual poor view them as rich, and in fact envy and hate them more than they do any banker. The disconnect between social reality and the self-explanatory discourse is, in such circumstances, total.

Likewise, the Marxist habit of interpreting ideas as stereotyped expressions of class interests is easily projected onto our historical memory. It bulldozes over a readily observable—but Marxistically inexplicable—fact: in Brazil, ideological discourse has almost never aligned with the objective interests of the social classes involved. In public education, textbooks, and so-called educational television programs, the Marxist reduction of cultural achievements to mere superstructures of class interest is now so deeply woven into everyday vocabulary that anyone trying to offer a different account of history can hardly even find a starting point, and risks sounding ridiculous when confronting the prevailing “common sense” (in the Gramscian sense of the term).

Quite understandably—though no less ironically—the more one’s intellectual horizon is confined to the canons of Marxist vulgate, the more violently one reacts to any suggestion that Marxist propaganda exists in Brazil, let alone the idea that communists hold any real power here. To be invisible, as René Guénon once noted, is of the very essence of power.

A second phase of indoctrination adds to the class stereotype the moral and emotional values needed to elicit approval or disapproval according to whether a given discourse seems to align with the “class interests” of the virtuous poor or the evil rich—regardless of any actual connection. For instance, discourse in favor of free enterprise—although it objectively supports the vast poor population that depends on the informal economy—is rejected as a defense of elite and multinational interests. Meanwhile, statist rhetoric—which scarcely touches the true interests of the rich and in fact empowers the omnipotent bureaucracy that impoverishes the nation through an extortionate tax burden—is readily embraced as expressing the “excluded.” Alienation thus gives way to hallucination, and not coincidentally, the anxiety produced by a vague intuition of madness is then exploited to stoke further hatred toward the stereotyped image of the “ruling class,” blamed for every ill and personified in individuals and groups that are, in fact, not dominant at all and function merely as scapegoats—such as the military, for example. So thoroughly do conventional symbols override factual perception that an event like the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre is passively accepted at face value as an anti-globalist demonstration, despite the support it receives from the UN—the very heart of the New World Order—and from the global NGO network that serves as the UN’s circulatory system, just as veins and arteries serve the heart.

P.S. — I have better uses for this weekly column than wasting it rebutting the latest defamatory outburst from Ms. Cecília Coimbra (O Globo, January 20). However, unwilling as I am to strike a pose of lofty silence, I’ve posted a reply to her and her comrades on my website, where I show how, in her furious ineptitude, she ends up proving what she intended to deny and denying what she hoped to prove. From this point on, no further explanations: any renewed attempt to portray my article “Torture and Terrorism” as an apology for torture will be met with a lawsuit.

0

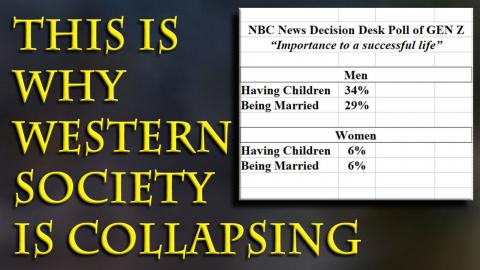

Blackpill_52

Blackpill_52

Better Bachelor

Better Bachelor![React: JOÃO CARVALHO NÃO SABE O QUE É FASCISMO [REVOLUSHOW] - João Eigen](https://cdn.mgtow.tv/upload/photos/2025/09/YXcSnwZzQwbRDiR5U9lb_12_c860c21a8b09d171d1e4cd1584ab61cf_image_thumb_high.jpg)

Sant77

Sant77

Log in to comment